This is a story of how even with the best of intentions,

forcing another to warp their life in order to fit a prevailing mold has

unforeseen as well as unfortunate consequences. Lue Gim Gong comes to America

from China in the second half of the nineteenth century. All his life he’s been

interested in breeding plants, but that passion doesn’t help the boy named

Double Brilliance fit in. Growing flowers is seen as a foolish pastime in rural

China, and when his uncle gives him a chance to go to Gold Mountain—the

U.S.—the innocent boy leaves his plants behind, only to land in Massachusetts

under the tutelage of a laudanum-addicted Christian spinster. Gim Gong does his

best to conform to Fanny’s expectations, not supporting his striking brethren,

converting to Christianity, and working in her father’s garden for nothing.

Fanny revels in teaching Lue, her budding career in education cut short by her

father’s demands years before. Lue becomes her creature, spending hours

discussing horticulture with her, halting the payments he’d been sending home

to China, and moving to Florida to continue his experiments. He develops Lue

Gim Gong oranges although he never profits from them, and is left out of Fanny’s

will, and can’t have the woman he wants. In China, his family has their own

twisting story, beset by ghosts and jealousy-inspired, spiteful relatives. Lue

Gim Gong always comes around to looking on the positive side, and goes on to

develop more new citrus strains. There are lots of well-researched details in

this book, but the fictional biography McCunn tells of one immigrant’s fight to

become a master horticulturist is not a happy story.

A slim memoir of Tobias’s early years on the prairie,Thunder and Mud is listed as a children's book, a look at a time gone by, brimming with the minutiae of rural life in homesteading days and a family bonded by love and hard work.

Esther Hobart Morris: The Unembellished Story of the Nation’s First Female Judge by Kathryn Swim Cummings

Although packed with historical details of the movements of

the famous South Pass City judge and what was occurring around her in

Sweetwater County, her homes in New York and Illinois, and the nation, as well

as pages of facts about all her relatives, the reader never really draws close

to Esther Hobart Morris. Less a failing of the author, I think it was

characteristic of the historical figure who came to be called the Mother of

Women’s Suffrage that few people really knew her beyond the myth that she

somehow stuffed forty people into her small log home to drink tea and twist the

arms of some male politicians until they promised to give women the vote in

Wyoming Territory. Like her doubtful conclusion that Sacagawea returned to the

Wind River Reservation and died there, this fabrication by Herman W. Nickerson

was amplified by Grace Raymond Hebard, who apparently desperately wanted some

female representation in a history told by males. But like the lore grown up

around cowboys, the West stands by its myths and Cummings is brave to attempt

debunking one of our favorites.

Billionaire Wilderness: The Ultra-Wealth and the Remaking of the American West by Justin Farrel

The son of a house cleaner, raised in Wyoming and now a

professor at Yale, Justin Farrel has unique built-in entry to the billionaires

of Jackson Hole. In interview after interview with the wealthy of Jackson Hole,

he brings to light their skewed perspective: how they think they can dress up

in costume like the locals to go have a few brews with people they believe are their

working class “friends”; how they buy land to offset taxes and their glaringly

over-the-top homes perched on mountains stripped bare of forest and wildlife

just to restrict growth in their little corner of paradise; how they support

environmental causes with lavish parties and big bucks but hold their noses and

turn their backs on the nonprofits that prop up the underpaid families who

clean their mansions and raise their children. This book didn’t present any new

information about the mega rich, it just reinforced what F. Scott Fitzgerald

wrote in 1926: "Let me tell you about the very rich.

They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does

something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are

trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to

understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are

because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves."

An Illustrated History of the Chinese In America by Ruthanne Lum McCunn

This slim volume is a concise history illustrated with

photos, maps, and drawings. Published in 1979 and suitable for adults or even

middle grades, there’s a lot of information on a still little known American

minority packed in its pages.

I See by Your Outfit: Historic Cowboy Gear of the Northern Plains by Tom Lindmier and Steve Mount

A lavishly researched and illustrated history of the Western

cowboy, Lindmier and Mount separate fact from Hollywood and dime novel fiction

in the description of everything from cowboy clothing, cowboy and horse gear,

to ranch life and roundups. My only complaint with the book is that with all

the explanation, the authors sometimes lost track of the fact that not every

reader of this book is familiar with the subject, and didn’t explain an

esoteric term that, in my case at least, could have used a few words of

clarification.

Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen by Sarah Bird

A white woman, Bird does a good job of finding a fictional

explanation of how a slave named Cathy Williams became a Buffalo Soldier named

William Cathay. Delving into Black/white, male/female, and U.S. Army/Native

American issues, the novel presents a portrait of a woman, granddaughter of a

captured African warrior queen, who refused to bow down and accept a role artificially

assigned to a Black woman.

Gathering From the Grassland: A Plains Journal by Linda M. Hasselstrom

Never having been to one of Hasselstrom’s writing retreats

but having heard much about her over the years, I was surprised to find that

through 320 pages and a year of journal entries of her life on the ranch and

what felt like intrusive delvings into the letters and journals of her parents,

in the end I should have been forewarned by her confession in the first entry

of the book that “I am wary of journals, even, or perhaps especially, my own.”

Some parts of the book shone, such as those dealing with the ecology of the land.

In many others, the author just seems tired and uncertain about the ultimate destiny

of the place she, childless and aging, fought so hard to keep.

Wolves of Eden by Kevin McCarthy

Three Irish

veterans, a Jew, and a noseless Indian prostitute meet up in the bloody West

following the bloody Civil War. Told in two voices, one a straight narrative

and one a confession written by one of the Irish men to the alcoholic Irish

superior officer sent to investigate the murder of a soulless post sutler and

his malicious wife in 1866 Dakota Territory, this is a story of how love (for a

brother, for a woman, or for a fellow soldier) endeavors to transcend the evils

of war, genocide, and the worst examples of how men deal with their fellow

human beings. Harrowing, gruesomely historically accurate, this book is not an

easy read, but it is a grippingly honest one.

Nighthawk Rising: A Biography of

Accused Cattle Rustler Queen Ann Bassett of Brown’s Park by Diana Allen Kouris

Called Queen

Ann because of her haughty demeanor, Ann Bassett and her siblings were raised

by their parents in remote Brown’s Park, Utah. Ann’s mother wanted to raise

cattle, and so the girls of the family were reared almost like cowboys when

they weren’t off to boarding school. In Butch Cassidy’s milieu and hunted by

the likes of the notorious Tom Horn, most small ranchers ended up branded

cattle rustlers as the big outfits tried to run them off the land the water.

From a time when maverick calves were considered fair game for anyone’s

branding iron to a time when the big ranchers overran and overgrazed the

countryside with cattle bearing their brand, it was difficult to keep up with

whose cows were whose on whose land. Some of what’s been written about Queen

Ann were attempts to shine a better light on the writer at her expense. Some of

it she owned up to later in life in her own unpublished autobiography. In

Nighthawk Rising, Diana Allen Kouris has tracked down many original sources of

material on Brown’s Park and its early denizens. Her extensively researched

book is a must read for outlaw fans, homesteader buffs, and women’s history enthusiasts.

The Which Way Tree by Elizabeth Crook

Ostensibly a

testimony concerning the whereabouts of a missing accused Confederate murderer,

this quirky book is an intimate peek into the lives of two orphan children in

Texas. Benjamin Shreve, the narrator of the testimony, and his half black

sister Sam, are on the trail of the panther that killed Sam’s mother and

disfigured the girl’s face with deep claw marks. Single-minded about finding

and killing the panther, Sam leads her brother and others who get swept up in her

quest for vengeance on an ambitious chase after the big cat. Benjamin doesn’t

paint an attractive picture of Sam: she’s lazy, stubborn, and argumentative.

But she’s his sister, and that fact determines that he will help her no matter

what. The characters in the book, including Ben’s mare, are finely drawn, and

the reader is as helplessly drawn along in Sam’s quest as the others who

accompany her in her pursuit of the panther.

A Fence Around Her by Brigid Amos

This novel,

billed a “clean read” and aimed at young adults, certainly doesn’t shy away

from adult themes. Fourteen-year-old Ruthie has the care of her emotionally

fragile mother while her father is at work in the gold mine in Bodie,

California. A town on the way to bust, there are still a few diehards working

there, and a few strangers who land in town looking for an opportunity to make

their fortunes. From the very first, Ruthie doesn’t trust the sinister Tobias

Mortlock, although her mother seems fascinated by him. Her father seemingly

oblivious to the situation, it falls mainly to Ruthie to try to rescue her

mother, a painter and former prostitute miserable in the small town and certain

from the way the townspeople treat her that when she dies she won’t even be

allowed inside the fence surrounding their cemetery. The insertion of

Catholicism seems sort of pasted into the narrative although it does serve as a

vehicle for Ruthie to at least lay eyes on the boy she’s interested in until

they can meet and get past the town’s prejudices, and perhaps to help the book sell as a Christian romance. This is a readable historical

for Young Adult+ audiences.

My Heart Lies Here by Laurie Marr Wasmund

A novel

“about” the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado in 1913 between miners of many

nationalities joining the United Mine Workers, and the militias brought in to

break a strike that led to them trying to wipe out the determined miners and

their families who hung on, sheltered in numbered tents, over the course of a

brutal winter. But it’s the characters who make this story come to life,

Christian Scott and her brother Alex, the young woman Pearl who appears on

their doorstep and falls in love with Alex, and the handsome Cretan miner

Theros who captures Christian’s heart. As dogged as the miners are, spunky heroine Christian matches them in disposition. Whatever I expected of this story, it

wasn’t a romance. This book is so good it deserves a wider readership. I think

a different cover would help, one that reflects the fact that this is an absorbing

story about people as much as Colorado and union mining history.

Thousand Pieces of

Gold by Ruthanne Lum McCunn

I bought this book as a fictional companion to my book

club’s selection, the nonfiction Poker

Bride. After reading both, it is apparent the two authors came away with two

different pictures of the subject, Lalu Nathoy better known as Polly Bemis.

Sold by her father in China during a period of famine, Lalu begins her period

of slavery in a brothel. She is sold to a wealthy Chinese merchant in Warrens,

Idaho, and then won in a poker game by gambler and saloon owner Charlie Bemis.

Named Polly because all Chinese prostitutes were called Polly, Lalu and

Charlie’s story is framed as a love match by McCunn, although there was no

doubt a clear-eyed financial aspect to their relationship. Charlie owns Polly’s

boardinghouse, ostensibly because the Chinese weren’t allowed to own property

although they could take over panned-out mining claims. When Polly has to be

spirited away to protect her from deportation in one of the times of anti-Chinese

laws, Charlie marries her and takes her ten miles away in the wilderness to

homestead. There seem to be pieces missing in this fictional telling of

historical events, such as whether getting shot in the face had more to do with

Charlie’s move away from Warren than protecting Polly, and the perhaps

clear-eyed conclusion that as a gambler he wasn’t used to the hard labor

required of a homesteader and that Polly was willing to shoulder most of the

burden. Old documents such as deeds and marriage certificates leave much open to

interpretation, and there are only a few records of what happened in Polly’s

life and none to say why, so this probably idealistic telling of an Idaho

pioneer woman’s story turns out to be a heartwarming read.

The Time It Never Rained

by Elmer Kelton

Even to his 1950s contemporaries, Charlie Flagg is an

anachronism. Amid the longest Texas drought in memory, he alone stands on his

own two feet, refusing to take government handouts to save his cattle. Life is

hard, and the years of drought test the boundaries of what makes a man, what

makes a marriage, and what makes a family. This is a deeply researched and

deeply felt Western, a Western Heritage Spur Award winner.

You are Respectfully

Invited to Attend My Execution by Larry K. Brown

The first Sweetwater County Historical Museum history

reading club book selection, this nonfiction work details the crimes, captures

and deaths of men lawfully executed in Wyoming Territory. Sources are cited at

the end of each chapter dealing with a single criminal, and it becomes chillingly

obvious that the West attracted more than its share of murderous psychopaths.

Not much past the days of executions as public entertainment, Brown captures

the efforts made to lend dignity to the proceedings. But though it’s hard to

imagine nowadays that a murderer had the opportunity to send invitations to his

hanging, Brown uncovered the documents proving that once it was so.

Wyoming by JP

Gritton

I picked up this book for its title. Although the novel

doesn’t have much to do with Wyoming, it

does paint a portrait of a certain kind of Western man, one

who refuses to grow up and goes through life blaming everyone around him for

his lack of success. In a long train of misfortune made worse by bad decisions,

it becomes apparent even his ex-con brother is more mature than Shelley Cooper.

“You wait long enough, everybody will let you down.” Shelley lets down everyone

he knows, and it’s a depressing ride along with him to the end of this story.

The Last Midwife by

Sandra Dallas

The Glovemaker by Ann Weisgarber

A look at the survival tactics of outlaw polygamous Latter-day

Saints in 1888 Utah, the main character in this book, Deborah Tyler, teeters

between sympathy for the people involved and resistance against blind obedience

to contemporary and historical Mormon doctrine. Survivors in a harsh landscape,

the people of Junction, a metaphorical stand-in for the Church, must ultimately

decide whether to stay or to go.

The Mapmaker’s

Daughter by Katherine Nouri Hughes

Although my favorite historical novels are those that teach

me something I don’t know about people or places in time, I found this book

about a 16th century girl kidnapped from Venice who rises from the harem to

become a Sultan’s daughter-in-law, a Sultan’s wife, and a Sultan’s mother, slow

going and too unfamiliar to absorb. Told from her viewpoint as she lies dying,

the point of the book is mostly as unfathomable as the mechanics of the Ottoman

Empire she is trying to explain. What was the purpose of her extensive European

and Turkish education? The library she is bequeathed by her old teacher and

that she tries to bequeath her heirs, is destroyed. In the end, she realizes

she was merely the tool of the dead Suleiman the Great and his desire to avoid

civil war by murdering all except the winner of those who might vie for the

throne.

Blood of the Prophets:

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows by Will Bagley

An exhaustively researched history of the Mormon Church and

the events and beliefs that led up to the slaughter of wagon train emigrants

traversing Utah in 1857, this book is a hard look at the nature of a religious

leader with feet of clay, the unquestioning obedience of such a man’s

followers, and the consequence of that man’s fiery rhetoric on a congregation

with a severe persecution complex. At almost 500 pages in hardback, be prepared

to pay attention because the reward for sticking with Bagley’s narrative is

great.

Settler’s Law by

D. H. Eraldi

I really liked this book about a “boy outlaw” who serves his

sentence and returns home to find squatters in his family’s cabin and his

mother and sister murdered. The only one of the stagecoach robber gang

surviving, Sett supposedly has knowledge of where the gold was hidden and in

danger not only from a Montana vigilante group but also from the murderers. An

abused half Blackfoot girl joins up with Sett because her dog likes him, hoping

he can show her the pass over the mountain to her people. The novel was

originally published by Berkeley, so it was hard for me to accept the easily

fixable errors in the ebook version: lightening for lightning, it’s as a possessive

of the pronoun, a jarring use of coolie for coulee, etc. A final edit would

have earned this Western five stars.

The Art of Love by

A. B. Michaels

A divorced woman and a man whose wife has disappeared meet

and fall in love in San Francisco following the Klondike Gold Rush. An

enjoyable historical romance with lots of period detail, although a bit

predictable.

The Kitchen Mistress by

Kathleen Shoop

Not too many references to the first two books in this

series, but enough to explain some of the odd relationships between the

characters in this one. In 1892 Katherine Arthur and her family are trying to

claw their way back to their former level of grandness, when they become

involved with Violet Pendergrass who’s trying in any manner she can to claw her

way to the top. Katherine, a seer, allows Violet to pull the wool over her eyes

a few too many times in her attempts to protect her family in a convoluted plot

about money, sex, and power.

Mashka by Sophia Gallegos

Much like Anne Frank’s story, this is the diary of a young

woman detailing how her hopes and longings for a bright future take flight while

she is physically held captive, prisoner to the stormy events of Europe at war.

Under the watch of Bolshevik soldiers, Grand Duchess Maria is reduced to

washing her family’s tattered laundry after they have lost almost everything to

the Revolution. The events leading to the murder of the entire Romanov family

are historical fact and Maria’s ultimate fate is as certain as Anne’s. But

still the reader is swept up in the daily events in the life of the doomed

heroine, one who resembles any other young woman who has let her feelings free

and fallen in love.

A Perfect Little World;

Nothing to See Here; The Family Fang by Kevin Wilson

I read a favorable review of The Family Fang, voted Best Book of the Year by Time, Amazon, People, Salon, and Esquire,

and so bought three Kevin Wilson novels on that basis. The three books share a

common theme: how being a parent can end up either suffocating or freeing the

children of the relationship. The difference in the three novels is just how

weird the adults might be, from really strange in The Family Fang, to largely indifferent parents who turn to a

caring stranger in Nothing to See Here,

to oddly normal-seeming parents who agree to a ten-year commitment living under

a microscope in a damaged doctor’s version of Utopia in A Perfect Little World. Kevin Wilson takes the common fear of a

parent—wondering whether what mom and dad do during the years their child lives

under their domination will damage or nurture the offspring—and turns it nightmarish.

In Wilson’s estimation, the line between the two results is sometimes blurred.

A Free State by

Tom Piazza

Living in one area for an entire lifetime can prove both restricting

and intensifying to a person’s understanding of history. A life spent in the

Rocky Mountain West means I’ve imbibed lots of cowboy, outlaw, Native American,

and Manifest Destiny history. As I get older, I find myself wanting to broaden

my perspective by searching out novels that will show me things I don’t know. I

don’t know much about the South. What I do know is that to this day, every once

in a while a prominent person is shamed in the media for wearing blackface. But

beyond the obvious boneheadedness of famous folks photographed mocking the

history of black people, I didn’t have a clue about the deeper significance of the

origin of blackface, the minstrel shows. By contrast, the author Tom Piazza, with

his extensive background in New Orleans, is more than capable of illuminating

the history of minstrelsy. In addition to the chilling details of slavery in

the South, Piazza spins a fascinating story of the stubborn obliviousness of

the North in the years preceding the Civil War, when even there the law bars black

men from appearing onstage. Instead white men with burnt cork applied to their

faces perform slavery-inspired songs extolling the supposed virtues of plantation

life. In A Free State one black man

escapes slavery with his banjo, and he’s such a good performer he’s hired to

perform onstage in Philadelphia despite the law. In the gradual peeling back of

some of the scales of racial illiteracy from the minstrel troupe’s eyes, the reader

also is schooled in the situation that led to the War and also in how a black

man is required to contort himself in order to survive in a culture determined to

rob him, in one way or another, of his very identity.

According to Kate

by Chris Enss

In this work of nonfiction, Chris Enss uses the handwritten

notes, letters, and interviews of Maria Izabella Magdolna, aka Mary Katharine

Horony, aka Kate Fisher, aka Kate Elder, aka Mrs. John Henry Holliday, aka Big

Nose Kate, aka Mary K. Cummings, to paint the facts of the life of the woman

who will always be tied to the history of Doc Holliday, the Earps, and the

shootout at the O.K. Corral. Kate left only her notes because she couldn’t

convince a publisher to give her the money she thought her tale deserved. So

until now, her portrait has largely been tinted in unflattering colors by historians

influenced by the story co-written by Wyatt Earp. In trying to make this a

modern story told with the modern sensibilities of a sex worker who chooses her

own destiny, Enss performs some contortions in an attempt to avoid calling Kate

a whore and her places of employment whorehouses. I wondered if Kate herself

would have taken such delicate steps to ensure her own reputation if it would

have helped to sell her book. It was also a bit awkward in places trying to

wedge Kate into venues such as opera houses contemporary to her but

undocumented that she actually attended. Otherwise, this small volume is a

competent telling of the facts of one woman’s life in the Old West.

The Giver of Stars by JoJo Moyes

The packhorse librarian program was a Works Progress Administration initiative that ensured literacy to the mountain people of Appalachia between 1935 and 1943. There is a lot of background detail about the changing relationships between men and women, mountaintop mining, and surviving the Depression. Along with growing a library in Kentucky, the women characters in this historical novel grow in knowledge, courage, maturity, and new relationships. A wonderful tale skillfully told.

The packhorse librarian program was a Works Progress Administration initiative that ensured literacy to the mountain people of Appalachia between 1935 and 1943. There is a lot of background detail about the changing relationships between men and women, mountaintop mining, and surviving the Depression. Along with growing a library in Kentucky, the women characters in this historical novel grow in knowledge, courage, maturity, and new relationships. A wonderful tale skillfully told.

The Atomic City Girls by Janet Beard

After reading this book, I think a more apt title would have been Atomic City since its focus is not really on the girls who worked on the secret World War Two project but more on the Tennessee government project itself. None of the characters with the exception of the black workers were portrayed sympathetically, although it’s understandable that the overwhelming constant reminders to keep tight lips might have something to do with suppressing the emotional impact of the story, keeping the reader at a distance as the truth was kept from the workers.

After reading this book, I think a more apt title would have been Atomic City since its focus is not really on the girls who worked on the secret World War Two project but more on the Tennessee government project itself. None of the characters with the exception of the black workers were portrayed sympathetically, although it’s understandable that the overwhelming constant reminders to keep tight lips might have something to do with suppressing the emotional impact of the story, keeping the reader at a distance as the truth was kept from the workers.

The Great Alone by Kristin Hannah

As if survival in backwoods Alaska isn’t hard enough for the unprepared, the author drops teenager Leni and her mother into the wilderness with an abusive, paranoid, alcoholic, former prisoner of war Vietnam veteran. Amazingly, Leni comes to love Alaska. It’s the only place her family has “settled” for long, and it’s the only place she has ever truly fit in. But they can’t ever let their guard down. In this book, Alaska is always ready to kill the unwary. While reading the novel, it’s obvious there isn’t going to be much of a starry-eyed happy ending. The author just keeps piling on precarious situations until the question becomes, who or what will try to destroy whom or what first?

Dreamers & Schemers: Profiles from Carbon County, Wyoming’s Past by Lori Van Pelt

This book imparts a lot of historic research about the characters who populated, or in some cases passed through, the locales of this south central Wyoming county. From mountain men to outlaws to politicians to a woman photographer, a woman hanged for cattle rustling, and a female physician who clung to the skullcap of executed criminal Big Nose George, there were some mighty interesting—if peculiar—folks living there.

This book imparts a lot of historic research about the characters who populated, or in some cases passed through, the locales of this south central Wyoming county. From mountain men to outlaws to politicians to a woman photographer, a woman hanged for cattle rustling, and a female physician who clung to the skullcap of executed criminal Big Nose George, there were some mighty interesting—if peculiar—folks living there.

The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier by Scott Zesch

Once Scott Zesch came upon the lonely grave of his great-great-great uncle Adolph Korn, he couldn’t rest until he uncovered the story of the boy who had been abducted at ten years old. Weaving the biographies of several Texas children abducted and traded around Indian Country in the years preceding Adolph’s disappearance in 1870, Zesch finds that most if not all of these child captives didn’t actually want to be rescued, and had an extremely difficult time adapting to “civilized” life if they were ransomed away from the tribes. It’s a compelling history, but Zesch has no more success than anyone else in answering precisely how little German immigrant children so quickly became Comanches.

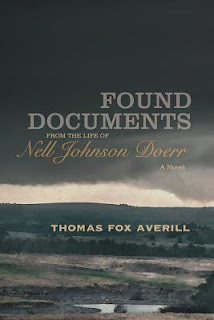

Found Documents from the Life of Nell Johnson Doerr by Thomas Fox Averill

If the reader weren’t warned that this story is fiction, it would be easy to believe it a true account of an abolitionist woman from Arkansas who moves to the free territory of Kansas, only to be widowed when her husband is murdered by Quantrill’s Raiders. Set adrift, Nell must find her own way in life and becomes fascinated by the creatures preserved in the Permian rocks making up the walls of her home’s foundation. Seeking more knowledge, she dares the disapproval of her neighbors to walk the muddy riverbanks, and eventually to start seeking out those educated in the lore of fossils in order to expand her own understanding. A finalist in the 2019 WILLA Awards from Women Writing the West, this book richly rewards the reader.

If the reader weren’t warned that this story is fiction, it would be easy to believe it a true account of an abolitionist woman from Arkansas who moves to the free territory of Kansas, only to be widowed when her husband is murdered by Quantrill’s Raiders. Set adrift, Nell must find her own way in life and becomes fascinated by the creatures preserved in the Permian rocks making up the walls of her home’s foundation. Seeking more knowledge, she dares the disapproval of her neighbors to walk the muddy riverbanks, and eventually to start seeking out those educated in the lore of fossils in order to expand her own understanding. A finalist in the 2019 WILLA Awards from Women Writing the West, this book richly rewards the reader.

Cherokee America by Margaret Venable

My review: The wealthy farm family at the center of this post-Civil War story is part Cherokee and part white, so the tale takes some unexpected turns for the reader steeped in white culture. There is also an examination of post-slavery acceptance of black men’s wandering affections, which seemed another oblique commentary on American history. A major focus on young men’s penises, which I expect is a lot more accepted in Native life, made me think those organs should have been characters in the story, although there are already many of those. Some of the action resembles a reworking of Native stories from the viewpoint of mixed heritage people. The pace of this story is slow and there are a lot of characters to follow. Not recommended for everyone, but for readers who want a distinct viewpoint on a historical period.

My review: The wealthy farm family at the center of this post-Civil War story is part Cherokee and part white, so the tale takes some unexpected turns for the reader steeped in white culture. There is also an examination of post-slavery acceptance of black men’s wandering affections, which seemed another oblique commentary on American history. A major focus on young men’s penises, which I expect is a lot more accepted in Native life, made me think those organs should have been characters in the story, although there are already many of those. Some of the action resembles a reworking of Native stories from the viewpoint of mixed heritage people. The pace of this story is slow and there are a lot of characters to follow. Not recommended for everyone, but for readers who want a distinct viewpoint on a historical period.

Gold Digger: The Remarkable Baby Doe Tabor by Rebecca Rosenberg

A rags-to-riches-to-rags story of the legendary Baby Doe Tabor, second wife of Colorado’s silver king, Horace Tabor. The details of Horace’s chafing at the ordinary life, his profligacy as a silver miner, and his fascination for Baby Doe is one thread of the story. The other is men’s fascination with Baby Doe. Even determined to make it on her own, she can’t resist falling in love with a man twice her age with his big dreams and deep pockets. Even though familiar with the basic points of the story, this was a fascinating look at the promise and sometimes dashed expectations of the West through the vagaries of fate through one woman’s life.

A rags-to-riches-to-rags story of the legendary Baby Doe Tabor, second wife of Colorado’s silver king, Horace Tabor. The details of Horace’s chafing at the ordinary life, his profligacy as a silver miner, and his fascination for Baby Doe is one thread of the story. The other is men’s fascination with Baby Doe. Even determined to make it on her own, she can’t resist falling in love with a man twice her age with his big dreams and deep pockets. Even though familiar with the basic points of the story, this was a fascinating look at the promise and sometimes dashed expectations of the West through the vagaries of fate through one woman’s life.

The Bermondsey Poisoner by Emily Organ

Once again Victorian era newspaper reporter Penny Green finds herself involved in racing to solve the mystery of the story she’s reporting, while trying to deny her attraction to the detective she keeps bumping into along the way, James Blakely. A good female sleuth novel with lots of period detail.

Once again Victorian era newspaper reporter Penny Green finds herself involved in racing to solve the mystery of the story she’s reporting, while trying to deny her attraction to the detective she keeps bumping into along the way, James Blakely. A good female sleuth novel with lots of period detail.

A Curious Beginning by Deanna Raybourn

A deft hand at portraying a delightful Victorian woman lepidopterist determined to travel the world and sample all its delights, the author also gives readers layers of mystery along with a dark, compelling hero. A fun read.

A deft hand at portraying a delightful Victorian woman lepidopterist determined to travel the world and sample all its delights, the author also gives readers layers of mystery along with a dark, compelling hero. A fun read.

Bird Woman (Sacajawea) the Guide of Lewis and Clark: Her Own Story Now Given First to the World by James Willard Schultz

This 1918 book tells the story of the Shoshone woman who guided Lewis and Clark’s Corp of Discovery to the Pacific Ocean in 1804-06. The basic outline is well known: a young captive sold to a French Canadian voyageur leads an expedition across uncharted territory with a baby in her arms, at several points saving the entire company. The book’s shortcoming is that the end relies entirely on Grace Hebard’s contention that Sacajawea came to the Wind River reservation and died there an old woman. The historical record indicates Sacajawea died in 1812 at Fort Manuel in present day South Dakota. So although there’s no indication of it in this book, the argument goes on.

This 1918 book tells the story of the Shoshone woman who guided Lewis and Clark’s Corp of Discovery to the Pacific Ocean in 1804-06. The basic outline is well known: a young captive sold to a French Canadian voyageur leads an expedition across uncharted territory with a baby in her arms, at several points saving the entire company. The book’s shortcoming is that the end relies entirely on Grace Hebard’s contention that Sacajawea came to the Wind River reservation and died there an old woman. The historical record indicates Sacajawea died in 1812 at Fort Manuel in present day South Dakota. So although there’s no indication of it in this book, the argument goes on.

A Free Man of Color by Barbara Hambly

I like nothing so much as a historical novel that can teach me something new. Such is Barbara Hambly’s portrayal of 1833 New Orleans, where Benjamin January, who has been living the life of a respected doctor in Paris, returns to New Orleans and its multitude of repressive layers of social connections. When a beautiful octoroon woman is murdered, there is no more handy suspect than the free black man who seems to know too much about some things and not enough to protect himself. An absorbing look into a different time and place in US history.

Not Just Any Man: Novels of Old New Mexico, Volume 1 by Loretta Miles Tollefson

I bought this book because I tried to read Volume 2 in the series as a stand-alone, and had trouble connecting the dots of the storyline of that book. The major portion of this book is a competent portrayal of the fur trapping business in nuevomexico under a young Mexican government. The protagonist, Gerald Locke Jr., a mixed race man passing as white, has escaped the problems of trying to live in Missouri as a free black amidst increasingly stringent slavery laws. He can’t figure out how else to get the grubstake he needs to obtain some land of his own to farm except to learn to trap beaver. His first winter trapping is an exercise in patience, putting up with the endless chatter of the loquacious Bill Williams. The second winter he joins a trapping company, learning more about the trade, some aspects of which he definitely doesn’t like. Along the way he rediscovers a beautiful mountain valley where he begins to dream of settling. He also makes a mortal enemy of a disturbed man who seizes any excuse to make trouble for Gerald and others, especially those he views as easy prey, male or female. In Taos, Gerald meets 15-year-old Suzanna Peabody, and they develop an enduring attraction. Suzanna has been schooled in Latin, not domestic duties, although she does like to garden. Gerald, even after Suzanna’s father has given permission for them to marry, continues to conceal the truth of his ancestry. Her godfather, Ramón Chavez, and Gerald form a partnership, and the three ascend the mountains to Gerald’s dream valley to begin their next adventure. I had a few problems with this book. No matter the probable custom that women marry young in nuevomexico, Suzanna’s father had grand plans for her. So it seemed incongruous that he would just allow her to marry a man she barely knew and head off for what he must have known would be a tough life for even the hardiest pioneer woman, even though Ramón agrees to do all the cooking—a commitment I had to wonder if the man would come to regret. And about Ramón: Suzanna’s godfather was Catholic, surely, and she Protestant? Was that even possible? Another instance that caused me to stop reading and question was Ramón’s casual observance that there was gold in the Moreno valley streams, a factoid that just seemed tossed into the story and was never picked up again, especially since I read Volume 2 first and there was no mention of gold in that book either. For the most part I enjoyed this book, although I could foresee big trouble ahead for these characters, given their differences, perhaps even bigger trouble than most pioneers had to face.

Not My Father’s House: Novels of Old New Mexico, Volume 2 by Loretta Miles Tollefson

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, Spain has ceded its New World Territory to Mexico, trade along the Santa Fe Trail has opened and all are welcome—if those such as fur trappers agree to pay a tax to the Mexican government on any goods produced on Mexican territory. Any arable land around the settlements has all been claimed, and after trying and discarding the beaver trapping life it’s difficult for a free man of color in nuevomexico to make a living at his preferred occupation of farming. Add in deciding to settle in a beautiful but remote and cold mountain valley, Indians who still claim that land as theirs, an older Mexican man who has been promised a full share in the rewards of a farm partnership, a young wife taught nothing much of practical value but steeped in a useless Latin education, plus a deranged trapper with a grudge against the settlers, and the problems just keep mounting. As I got deeper into the book, I wondered how the husband, Gerald Locke Jr., and his partner, Ramón Chavez, managed to put up with young Suzanna’s moods and temper. Ramón has to abandon his own work to cook all the meals, and Gerald must maintain a grim silence, if he can’t manage an actual cheerful demeanor, in the face of his wife’s growing unhappiness as winter descends and she finds herself pregnant in a dark little cabin. I kept having to remind myself as I read that she was 16 years old and probably suffering from what today we would identify as SAD and postpartum depression. But it was a difficult path for this reader to walk with her. I also had questions about the writing that were unanswerable without having read the first in this series, Not Just Any Man: Novels of Old New Mexico, Volume 1. How did these so-different people end up together? Why did Suzanna’s father give her permission to marry at her young age and especially after having spoiled her for anything but a studious life? How did Gerald and Ramón, depicted as mostly clear-eyed characters, expect such an ill-equipped little girl to handle life in a dark, snowy, remote location, actually named the Moreno (black) valley, with just them for company? Did they have any idea of Suzanna’s emotional problems before they were stranded in the mountains by the weather? Did Suzanna really not have a clue concerning her husband’s true ancestry? And what version of mad compulsion could cause even a villain as dark as Enoch Jones to stalk this family for such an extended period of time? I thought as I read that even far advanced in pregnancy, there was nothing to prevent Suzanna returning to her father in Taos for the baby’s birth, on a travois if necessary. As evidenced by her repeated stubborn efforts to plant corn in the mountains, deep down did she really wish to finally do the hard thing—grow up—and not take the easy path once again by giving in and returning to her father’s house? This is a well-researched novel. The details about early New Mexico are fascinating. The characters are well-rounded, and some of the extremely difficult situations facing early Western settlers become evident. But without giving away any details, I felt the ending seemed abrupt and sort of pasted on the book. I would caution readers not to try and read this book as a stand-alone. It truly is Volume 2 in the Novels of Old New Mexico, a continuation of the lives of the characters begun in Volume 1. I look forward to reading the planned Volume 3 in the series, where I trust the author will resolve all my questions.

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, Spain has ceded its New World Territory to Mexico, trade along the Santa Fe Trail has opened and all are welcome—if those such as fur trappers agree to pay a tax to the Mexican government on any goods produced on Mexican territory. Any arable land around the settlements has all been claimed, and after trying and discarding the beaver trapping life it’s difficult for a free man of color in nuevomexico to make a living at his preferred occupation of farming. Add in deciding to settle in a beautiful but remote and cold mountain valley, Indians who still claim that land as theirs, an older Mexican man who has been promised a full share in the rewards of a farm partnership, a young wife taught nothing much of practical value but steeped in a useless Latin education, plus a deranged trapper with a grudge against the settlers, and the problems just keep mounting. As I got deeper into the book, I wondered how the husband, Gerald Locke Jr., and his partner, Ramón Chavez, managed to put up with young Suzanna’s moods and temper. Ramón has to abandon his own work to cook all the meals, and Gerald must maintain a grim silence, if he can’t manage an actual cheerful demeanor, in the face of his wife’s growing unhappiness as winter descends and she finds herself pregnant in a dark little cabin. I kept having to remind myself as I read that she was 16 years old and probably suffering from what today we would identify as SAD and postpartum depression. But it was a difficult path for this reader to walk with her. I also had questions about the writing that were unanswerable without having read the first in this series, Not Just Any Man: Novels of Old New Mexico, Volume 1. How did these so-different people end up together? Why did Suzanna’s father give her permission to marry at her young age and especially after having spoiled her for anything but a studious life? How did Gerald and Ramón, depicted as mostly clear-eyed characters, expect such an ill-equipped little girl to handle life in a dark, snowy, remote location, actually named the Moreno (black) valley, with just them for company? Did they have any idea of Suzanna’s emotional problems before they were stranded in the mountains by the weather? Did Suzanna really not have a clue concerning her husband’s true ancestry? And what version of mad compulsion could cause even a villain as dark as Enoch Jones to stalk this family for such an extended period of time? I thought as I read that even far advanced in pregnancy, there was nothing to prevent Suzanna returning to her father in Taos for the baby’s birth, on a travois if necessary. As evidenced by her repeated stubborn efforts to plant corn in the mountains, deep down did she really wish to finally do the hard thing—grow up—and not take the easy path once again by giving in and returning to her father’s house? This is a well-researched novel. The details about early New Mexico are fascinating. The characters are well-rounded, and some of the extremely difficult situations facing early Western settlers become evident. But without giving away any details, I felt the ending seemed abrupt and sort of pasted on the book. I would caution readers not to try and read this book as a stand-alone. It truly is Volume 2 in the Novels of Old New Mexico, a continuation of the lives of the characters begun in Volume 1. I look forward to reading the planned Volume 3 in the series, where I trust the author will resolve all my questions.

Miss Royal's Mules by Irene Bennett Brown

Author Irene Bennett Brown has nailed the character of Jocelyn Belle Royal, the title character in Miss Royal’s Mules, a 24-year-old woman teetering on the thin edge of spinsterhood. Jocelyn is equal parts naïf and determined turn-of-the-20th-century modern woman, and the glimpses we get into the formation of this young woman’s character—from a surgically repaired deformity, to a difficult but much-loved grandmother, to a much-absent father who ultimately loses the farm Jocelyn spent years building up—make for fascinating reading. Jocey seldom has a bad word for anyone, which doesn’t prevent her from thinking the worst of some of the men in her lives as she tries to puzzle out what they might be up to now. And there’s much to puzzle an unworldly woman as the story progresses. Her boss, Whit Hanley, disappears from the mule drive Jocey insisted on joining as cook and wagon driver; his friend Sam Birdwhistle abandons her after the two of them finally succeed in getting the mules to their intended destination at Nickel Hill ranch; and her childhood friend Tosten Pladson turns up in a new guise as a handsome rodeo rider and Western artist named Pete. I much enjoyed this novel, with a couple of minor caveats: some of the external historical events seem uncomfortably wedged into the story, and the blurb on the back cover of the book would have done better with more hints of what’s inside instead of broad swathes of the plot. But the story itself is a welcome addition to the historical genre.

Enemy Women by Paulette Jiles

This 2002 novel is a piece of the story of the Civil War I had not seen closely examined in fiction before. Were Southern women imprisoned by Union forces? How would a former belle, daughter of a judge and a teacher who reads law books and tries to maintain neutrality as the war waxes and wanes around them, cope with being arrested and detained in a federal prison, accused of aiding Rebel spies? Each chapter begins with snippets of historical accounts of the war, and interspersed throughout are sharply drawn portraits of the senselessness and cruelty of men who learn to kill. So when heroine Adair Colley finds love in the prison camp, can she believe anything will ever come of her promise to a Union officer? Even after she escapes, can she find her way back home and ever hope anything might be the way it used to be? An absorbing novel.

The Color of Lightning by Paulette Jiles

The lives of a freed black man, his wife and children, a Quaker Indian Agency employee, and some groups of Kiowa and Comanche intersect in Texas near the end of the Civil War in this 2009 novel. The situation for these people becomes very rapidly very dire. Quite a few Goodreads reviewers said they couldn't finish this book because of the violence. The language of the poet author is lyrical, even sometimes when describing horrific scenes of death and mutilation. Every character is drawn fine; there's no question of the weight of anyone's background, their preconceived notions, or motives for their actions. They're on a collision course, and the only question becomes, Will any of them survive? This isn't a pretty book or a comforting book. It is a book that makes readers pull back the curtain to examine history a bit more closely, a book that forces us to relinquish some of the gauzy myths surrounding white settlement of the West.

The lives of a freed black man, his wife and children, a Quaker Indian Agency employee, and some groups of Kiowa and Comanche intersect in Texas near the end of the Civil War in this 2009 novel. The situation for these people becomes very rapidly very dire. Quite a few Goodreads reviewers said they couldn't finish this book because of the violence. The language of the poet author is lyrical, even sometimes when describing horrific scenes of death and mutilation. Every character is drawn fine; there's no question of the weight of anyone's background, their preconceived notions, or motives for their actions. They're on a collision course, and the only question becomes, Will any of them survive? This isn't a pretty book or a comforting book. It is a book that makes readers pull back the curtain to examine history a bit more closely, a book that forces us to relinquish some of the gauzy myths surrounding white settlement of the West.

Stormy Weather by Paulette Jiles

This Depression Texas novel, published in 2007, follows the fortunes of the women of the Stoddard family as they try various means of just staying alive, from learning to drive a tractor to betting on horses to investing in long-shot oil wells. After following gambler and oilfield freighter Jack Stoddard from one strike to another, the women move to Elizabeth Stoddard's family farm, which she has built up in her memories as a refuge. What the Stoddards find is a deserted house almost falling down and neglected fields overgrown with brush. But what Stoddards don't do is give up, and they fight on through trials ranging from drought to accidents to dust storms. This character-driven novel, like an old country song, is a portrait of hard times and the people who don’t give up hope.

This Depression Texas novel, published in 2007, follows the fortunes of the women of the Stoddard family as they try various means of just staying alive, from learning to drive a tractor to betting on horses to investing in long-shot oil wells. After following gambler and oilfield freighter Jack Stoddard from one strike to another, the women move to Elizabeth Stoddard's family farm, which she has built up in her memories as a refuge. What the Stoddards find is a deserted house almost falling down and neglected fields overgrown with brush. But what Stoddards don't do is give up, and they fight on through trials ranging from drought to accidents to dust storms. This character-driven novel, like an old country song, is a portrait of hard times and the people who don’t give up hope.

News of the World by Paulette Jiles

It took a while to raise the same interest in this 2016 Jiles novel as in the others of her previous historical works. But once reeled in by the story of an old former newspaperman and a young girl reluctant to be rescued from the Kiowas, the reader is truly hooked. Captain Kidd, who makes a living traveling around Texas reading articles gleaned from different newspapers for a dime a head to assemblages of people in search of an evening's entertainment, accepts fifty dollars in gold to return Johanna Leonberger to her relatives after she spent four years in captivity. The journey of this old man and ten-year-old girl, across Texas as well as delving into their own personalities, makes for fascinating reading.

It took a while to raise the same interest in this 2016 Jiles novel as in the others of her previous historical works. But once reeled in by the story of an old former newspaperman and a young girl reluctant to be rescued from the Kiowas, the reader is truly hooked. Captain Kidd, who makes a living traveling around Texas reading articles gleaned from different newspapers for a dime a head to assemblages of people in search of an evening's entertainment, accepts fifty dollars in gold to return Johanna Leonberger to her relatives after she spent four years in captivity. The journey of this old man and ten-year-old girl, across Texas as well as delving into their own personalities, makes for fascinating reading.

These Is My Words: The Diary of Sarah Agnes Prine, 1881-1901 by Nancy E. Turner

When Sarah Prine's father takes it into his head to move his family from California to Arizona Territory, they become one of those involved in the westward migration who can't seem to settle but are always looking beyond the horizon for something easier or better or more lucrative than what they found at the last location. Sarah's diary details her personal growth against a big landscape of settlers, Indians, Mexicans, outlaws, soldiers, and various other characters. Sarah goes from being a girl on a wagon train to a wife and mother on a ranch made successful after years of hard work and determination. Through it all, the details of the struggles of everyday life shine against Sarah's lifelong goal of becoming educated.

When Sarah Prine's father takes it into his head to move his family from California to Arizona Territory, they become one of those involved in the westward migration who can't seem to settle but are always looking beyond the horizon for something easier or better or more lucrative than what they found at the last location. Sarah's diary details her personal growth against a big landscape of settlers, Indians, Mexicans, outlaws, soldiers, and various other characters. Sarah goes from being a girl on a wagon train to a wife and mother on a ranch made successful after years of hard work and determination. Through it all, the details of the struggles of everyday life shine against Sarah's lifelong goal of becoming educated.

The Star Garden: A Novel of Sarah Agnes Prine by Nancy E. Turner

This continuation of Sarah's diary covers the years 1906-1908. A mature woman in this novel, Sarah must contend with her grown children's love lives, the question of whether she wants to get romantically involved herself, her cattle getting rustled, a neighbor who was once a suitor since turned murderous, and an improbable semester spent studying at a college in Tucson. The characters' lives are all in the particulars of their losses and triumphs, and once again the author makes the reader step in to the story and care what happens.

This continuation of Sarah's diary covers the years 1906-1908. A mature woman in this novel, Sarah must contend with her grown children's love lives, the question of whether she wants to get romantically involved herself, her cattle getting rustled, a neighbor who was once a suitor since turned murderous, and an improbable semester spent studying at a college in Tucson. The characters' lives are all in the particulars of their losses and triumphs, and once again the author makes the reader step in to the story and care what happens.

The Beaten Territory by Randi Samuelson-Brown

Like Milana Marsenich's Copper Sky, this is a novel of a Western mining town and the people who populate the world beneath the surface prosperity. And it ain't a pretty picture. The Ryan family survives in Denver in the 1880s any way they can, as bordello owners, prostitutes, gamblers, and cheap watered booze suppliers. The trick is in not getting snared by whiskey, laudanum, or the opium offered by the Chinese. Into this world steps Pearl, daughter of deceased Claire Ryan, niece of Annie and her brothers Jim and John, fresh out of the Home of the Good Shepherd and welcome to join her cousins Julia and May by hooking to earn her keep. The Ryans get involved in some shady dealings courtesy of a crooked cop and a slumming society woman, and the nearest thing to a happy ending occurs when any of them merely survives to see another day.

Like Milana Marsenich's Copper Sky, this is a novel of a Western mining town and the people who populate the world beneath the surface prosperity. And it ain't a pretty picture. The Ryan family survives in Denver in the 1880s any way they can, as bordello owners, prostitutes, gamblers, and cheap watered booze suppliers. The trick is in not getting snared by whiskey, laudanum, or the opium offered by the Chinese. Into this world steps Pearl, daughter of deceased Claire Ryan, niece of Annie and her brothers Jim and John, fresh out of the Home of the Good Shepherd and welcome to join her cousins Julia and May by hooking to earn her keep. The Ryans get involved in some shady dealings courtesy of a crooked cop and a slumming society woman, and the nearest thing to a happy ending occurs when any of them merely survives to see another day.

And Only to Deceive by Tasha Alexander

I picked up this book at the Wyoming Writers Conference where Ms. Alexander and her author husband were session presenters. Although other American women authors must write about an English amateur sleuth in Victorian England, as an amateur reader of Victorian female sleuths I think she did a good job of always having her heroine remain in character. Lady Emily, although feeling constrained constantly by the mores of her times, and especially by her social climber mother, always finds a way to accomplish her goals as she inches toward the realization that the state of widowhood that by turns stifles her and frees her is no accident. But by the end of this novel I felt a bit stifled myself by the character of Lady Emily. I never did find the quality that made me empathize with her or her situation. I think there are 14 books in the series so far, but I only picked up one other to test Ms. Alexander's remark that her writing had improved over the years. And Only to Deceive was an interesting investment, although I doubt if I will buy the rest.

I picked up this book at the Wyoming Writers Conference where Ms. Alexander and her author husband were session presenters. Although other American women authors must write about an English amateur sleuth in Victorian England, as an amateur reader of Victorian female sleuths I think she did a good job of always having her heroine remain in character. Lady Emily, although feeling constrained constantly by the mores of her times, and especially by her social climber mother, always finds a way to accomplish her goals as she inches toward the realization that the state of widowhood that by turns stifles her and frees her is no accident. But by the end of this novel I felt a bit stifled myself by the character of Lady Emily. I never did find the quality that made me empathize with her or her situation. I think there are 14 books in the series so far, but I only picked up one other to test Ms. Alexander's remark that her writing had improved over the years. And Only to Deceive was an interesting investment, although I doubt if I will buy the rest.

Wild Migrations: Atlas of Wyoming’s Ungulates by

March 28, 2019—I-80 has become a killing field. Outside of Green River lies a dead hawk in the median, striped tail feathers fluttering in the breeze. The death toll mounts near Evanston: many mule deer carcasses line the roadside, and the pronghorn count continues to rise from the Lyman exit westward. Especially near the Bear River exit, many antelope apparently tried to follow the plowed pavement to cross the interstate. Many failed. Speeding past in a vehicle at 75 miles an hour, it becomes difficult to differentiate all the brown bodies, to tell one species from another, but I could swear I also saw one coyote and one mountain lion lying lifeless beside the road. The snow is mostly still deep along the fences, but in one cleared patch there was a bunch of pronghorn, excellent runners but not good jumpers, bunching up against the wire and looking at each other while apparently trying to decide what to do next. Wild Migrations: Atlas of Wyoming’s Ungulates details the yearslong effort to map and document the movements of the last of the nation’s migrating wild herds. Wyoming is lucky in being one of the final mostly open landscapes, but housing developments, roads, oil and gas infrastructure, and even backcountry skiers along with other human disturbances, threaten to choke off the remaining segments of paths first documented as the transcontinental railroad sliced the unimaginably huge bison herd into north and south groups before people almost succeeded in exterminating them completely. There are several groups working to conserve the migration corridors, take down impassable fencing, as well as build tunnels and overpasses at key pavement points. For those interested—as all of us who live here should be—in the background, history, science, and some rays of hope for conserving Wyoming’s wild populations, this book is highly recommended.

The Swan Keeper by Milana Marsenich

Eleven-year-old Lillian Connelly’s name is a diminutive of the Greek “Elizabeth,” meaning God’s oath, or in the original Hebrew “Elisheva,” or my God is an oath. Throughout her tumultuous eleventh year, Lilly witnesses the deaths and injury of a flock of her beloved swans, the murder of her father, the brain injury of her mother, and the awakening of a deeper feeling for her childhood friend. She comes to realize the growing injury to herself that comes from the fact that no one believes her account of who is responsible for all the devastation. Throughout a long year where she comes to identify with one of the injured swans that also refuses to give up, Lilly must keep a stubborn, grownup faith in herself as she bit-by-bit uncovers photographic evidence left by her father, that her damaged mother has buried another man’s long history of inexplicable violence and crimes against man and nature. There is some beautiful writing in this story, and despite descriptions of the poverty of Lilly’s family there is also the richness of her family’s imaginative, poetic accounts of why she is and why things are. The pace of the book is a bit slow, but the reader has time to be drawn into the majesty of nature and Lilly’s Montana surroundings.

Eleven-year-old Lillian Connelly’s name is a diminutive of the Greek “Elizabeth,” meaning God’s oath, or in the original Hebrew “Elisheva,” or my God is an oath. Throughout her tumultuous eleventh year, Lilly witnesses the deaths and injury of a flock of her beloved swans, the murder of her father, the brain injury of her mother, and the awakening of a deeper feeling for her childhood friend. She comes to realize the growing injury to herself that comes from the fact that no one believes her account of who is responsible for all the devastation. Throughout a long year where she comes to identify with one of the injured swans that also refuses to give up, Lilly must keep a stubborn, grownup faith in herself as she bit-by-bit uncovers photographic evidence left by her father, that her damaged mother has buried another man’s long history of inexplicable violence and crimes against man and nature. There is some beautiful writing in this story, and despite descriptions of the poverty of Lilly’s family there is also the richness of her family’s imaginative, poetic accounts of why she is and why things are. The pace of the book is a bit slow, but the reader has time to be drawn into the majesty of nature and Lilly’s Montana surroundings.

Barkskins by Annie Proulx

Living in the West, it has become more difficult to get out in the countryside and just enjoy the solitude. Oilfield roads and tracks scar the land everywhere, brown metal gas infrustructure is widespread, and even on the weekends when it should be quiet there’s never a moment when you don’t meet trucks coming at you on what used to be the back roads. When I moved briefly to Oregon and began looking into the history of the Northwest, one of the things that really struck me was reports of the incredulous reaction of the Natives to the absolute insane frenzy of the white men to harvest every single salmon in the Columbia. In Oregon it was also explained that the land has been logged off two and three times since white settlement, and all those Doug firs of identical height seeming to choke the hillsides were planted by logging companies to replace clearcuts. It still didn’t occur to me, until reading this book, that all of this rapacious behavior has been going on since the first Europeans landed here, and no matter what, is not likely to stop because as one of the ultimate characters in this epic family saga thinks, “they had been looking at human extinction.” This book is a masterpiece. All the characters are as fully drawn as the reader is, hurtling toward the end. Immerse yourself in this book. Learn the sad lesson the author teaches. Just don’t go looking for happily ever after here.

Living in the West, it has become more difficult to get out in the countryside and just enjoy the solitude. Oilfield roads and tracks scar the land everywhere, brown metal gas infrustructure is widespread, and even on the weekends when it should be quiet there’s never a moment when you don’t meet trucks coming at you on what used to be the back roads. When I moved briefly to Oregon and began looking into the history of the Northwest, one of the things that really struck me was reports of the incredulous reaction of the Natives to the absolute insane frenzy of the white men to harvest every single salmon in the Columbia. In Oregon it was also explained that the land has been logged off two and three times since white settlement, and all those Doug firs of identical height seeming to choke the hillsides were planted by logging companies to replace clearcuts. It still didn’t occur to me, until reading this book, that all of this rapacious behavior has been going on since the first Europeans landed here, and no matter what, is not likely to stop because as one of the ultimate characters in this epic family saga thinks, “they had been looking at human extinction.” This book is a masterpiece. All the characters are as fully drawn as the reader is, hurtling toward the end. Immerse yourself in this book. Learn the sad lesson the author teaches. Just don’t go looking for happily ever after here.

Copper Sky by Milana Marsenich

Coming from an immigrant coal miner background myself, I expected to find some similar points of reference in the copper mining town of early twentieth century Butte, Montana. There seem to be none. My grandparents came to a company town where night classes taught English and citizenship, the women competed for prizes in turning the desert into gardens that reminded them of their European homeland, and the second generation was Anglicized into model Americans with familiar names. Although it’s highly probable that the people who lived in the coal town of my childhood remember their youth through Mayberry-ized retellings that reinforce an impossibly rosy setting, nothing prepared me for the almost sci-fi dystopian setting of Copper Sky. People in this story are trapped in claustrophobic fates that resemble the twistings and turnings of a dark mine tunnel. The soil itself is poisoned, children are abandoned, women are imprisoned in prostitution and those who dream of a better life discouraged by a paternalistic society afraid to let them go, and men left with the choice of going to war or going to work down in the mines. The people in this story can’t admit the truth to themselves, and few can imagine even trying for a different life. Despite some poetic passages and the author’s surprise creative use of language, I found this a really difficult book to read. Nevertheless it’s compelling enough that I continued, and was rewarded in the end. The conclusion does rescue the narrative, like a ray of sunshine piercing the oppressive copper cloud.

Coming from an immigrant coal miner background myself, I expected to find some similar points of reference in the copper mining town of early twentieth century Butte, Montana. There seem to be none. My grandparents came to a company town where night classes taught English and citizenship, the women competed for prizes in turning the desert into gardens that reminded them of their European homeland, and the second generation was Anglicized into model Americans with familiar names. Although it’s highly probable that the people who lived in the coal town of my childhood remember their youth through Mayberry-ized retellings that reinforce an impossibly rosy setting, nothing prepared me for the almost sci-fi dystopian setting of Copper Sky. People in this story are trapped in claustrophobic fates that resemble the twistings and turnings of a dark mine tunnel. The soil itself is poisoned, children are abandoned, women are imprisoned in prostitution and those who dream of a better life discouraged by a paternalistic society afraid to let them go, and men left with the choice of going to war or going to work down in the mines. The people in this story can’t admit the truth to themselves, and few can imagine even trying for a different life. Despite some poetic passages and the author’s surprise creative use of language, I found this a really difficult book to read. Nevertheless it’s compelling enough that I continued, and was rewarded in the end. The conclusion does rescue the narrative, like a ray of sunshine piercing the oppressive copper cloud.

This Scorched Earth by William Gear

In just the few short years during and after the Civil War, members of the Hancock family are changed utterly. It was difficult to lay this book aside without finishing the entire 700+ pages. The author has so piercingly drawn his characters and their situations that the reader is drawn inside the story and only with utmost reluctance lets go. This novel is different from anything else this author has written in his wide and long career. If you’re familiar with his genre work, read it without preconceptions or expectations. Just read it. You’ll be richly rewarded.

In just the few short years during and after the Civil War, members of the Hancock family are changed utterly. It was difficult to lay this book aside without finishing the entire 700+ pages. The author has so piercingly drawn his characters and their situations that the reader is drawn inside the story and only with utmost reluctance lets go. This novel is different from anything else this author has written in his wide and long career. If you’re familiar with his genre work, read it without preconceptions or expectations. Just read it. You’ll be richly rewarded.

I read this book expecting to be enchanted by the main character, the daughter of Byron and supposedly a genius in her own right. But between her mother’s control, society’s constraints, Ada’s poor health and her own reluctance to test the boundaries, I don’t think her expectations or my own were ever met. The descriptions of the times, the characters, their dress and manners were all fascinating after we get past the explanation of her early life and her mother’s bad experience with marriage. But ultimately the Enchantress herself failed to bewitch me.

Finding True Home (American Dream) by Heidi M. Thomas

Once again, Heidi Thomas mines her family’s history to fictionalize life in rural 20th century Montana. This particular story documents the tribulations of a German immigrant woman to fit in to a culture where she can’t seem to find her footing among her neighbors’ post-war prejudice, a husband unable to verbalize his feelings, and eventually three children very different in personality from her and from each other. Anna Moser and her American husband, Neil, are willing to face all the arduous work involved and any hardship nature or ranch life can throw at them, in order to hang onto the land. A child of undemonstrative parents, Anna tries to be the best parent she can with her own children, but as they grow up and away from her, over and over again Anna’s response is to clutch much too hard in an effort to keep them near.

Flight of the Hawk: The River (A Novel of the American West) by W. Michael Gear

Flight of the Hawk: The River (A Novel of the American West) by W. Michael GearIn this novel of the early Western fur trade, the mysterious John Tylor serves as the hook on which hangs all the adventures of Manuel Lisa’s company’s ascent of the Missouri. Who is John Tylor and why is he on the run? If he’s in hiding from someone or something, why does he use his own name? It comes to light that he isn’t very successful in running from the price on his head. He can’t hide the fact that he’s obviously educated, even if he is dressed in rags. Yet he fits in well with most of the voyageurs, and pulls his weight arduously poling or pulling Lisa’s boats up the Missouri. Is he perhaps a spy for the competition? It seems he knows his way around Indians, and has even spent time in Santa Fe. Tylor wants only to vanish into the wilderness. Can Tylor evade his pursuers? Lisa trust Tylor to put the company’s interests first? Flight of the Hawk is a thoroughly enjoyable novel of American history. My single concern, no fault of the author, was the poor copy editing of this work. Perhaps the publisher will take note, and that situation will improve with volumes Two and Three of The River trilogy.

Yellowstone Has Teeth by Marjane Ambler

I bought this book at a Wyoming Writers conference, along with another memoir, Lucy Moore's Into the Canyon, Seven Years in Navajo Country. The two books are similar in theme: a woman in a new relationship chooses to spend time in isolation from her larger culture while learning to survive and grow and learning to fit in to a smaller, closer-knit culture that's totally foreign to her. Not incidentally, a background theme of both stories is the idea of trust. Learning to trust and depend on others, sometimes for sheer survival, is a facet of the growth of the narrators. The love stories underlying the main narrative of "woman against nature" are just one of the joys of reading these books.

Goodnight, Oregon by B.K. Froman

Do you like Oregon, or quirky characters, or higher education? How about a story of the stories that bring about a young woman's growth from a childhood of rural struggle to the doors that open after a years-long endeavor to attain the degrees that ultimately make a reach for the stars possible? For Stiks (Sophia) Bolton, it's a journey peopled by those she loves, but doesn't always completely understand. After skipping two grades in elementary school, it's a rapid rise for a girl who doesn't always fit in. As she matures, she has to extend tolerance to those she lives with, studies with, learns from, and works alongside. Her light really begins to shine when she takes to the late night airwaves to explore some of the events that furnished the foundation for the life she's determinedly building. Stiks rarely does things the way society might approve, but somehow manages to find the way to come out a winner. This book grabs you early and doesn't let go. I was given Goodnight, Oregon for an honest review. I wholeheartedly recommend it.

Do you like Oregon, or quirky characters, or higher education? How about a story of the stories that bring about a young woman's growth from a childhood of rural struggle to the doors that open after a years-long endeavor to attain the degrees that ultimately make a reach for the stars possible? For Stiks (Sophia) Bolton, it's a journey peopled by those she loves, but doesn't always completely understand. After skipping two grades in elementary school, it's a rapid rise for a girl who doesn't always fit in. As she matures, she has to extend tolerance to those she lives with, studies with, learns from, and works alongside. Her light really begins to shine when she takes to the late night airwaves to explore some of the events that furnished the foundation for the life she's determinedly building. Stiks rarely does things the way society might approve, but somehow manages to find the way to come out a winner. This book grabs you early and doesn't let go. I was given Goodnight, Oregon for an honest review. I wholeheartedly recommend it.

Walk the Promise Road: A Novel of the Oregon Trail by Anne Schroeder