(This is a

reprint of an essay originally published on Andrea Downing's

blog.)

Native American

Slavery

by Alethea Williams

In sofar as the

taking of captives and reducing them to slaves was concerned the Apache

acquired this custom from the Spaniard or Mexican, and it is safe to say that

during the period of which I write there was not a settlement in the valley of

the Rio Grande that did not number among the inhabitants a large number of

Apache and Navajo Indian slaves.

—Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The Leading Facts of New Mexican History, Torch Press, 1917

|

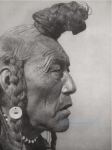

Photo of a

Blackfoot by Edward Curtis, with a hairstyle described in Naapiikoan Winter as

one worn by the character Saahkómaapi (Young Man), Beaver Bundle Man to the

Inuk’sik band of the Piikáni, and the band’s Dreamer.

|

The primary female character in my novel, Náápiikoan Winter, is abducted as a child and later traded into slavery. She is abducted by Apaches, sold by Utes, and enslaved by other tribes including the Piikáni. Was it true that Native Americans learned this practice from contact with the Spaniards, as the quotation that opens my book asserts?

Although it’s true Christopher

Columbus started an unholy tradition by enslaving over 500 Indians, an article

on the website Oxford Research

Encyclopedia: American History by Christina Snyder says, “The history of

American slavery began long before the first Africans arrived at Jamestown in

1619. Evidence from archaeology and oral tradition indicates that for hundreds,

perhaps thousands, of years prior, Native Americans had developed their own

forms of bondage.” Indians captured women and children to replace the up to 90%

of their people killed by war and diseases they had no defense against. In an

article for Slate, Rebecca Onion says

“Native types of enslavement were often about kinship, reproductive labor, and

diplomacy, rather than solely the extraction of agricultural or domestic labor.”

All Native tribes that I know of

were called “The People.” What this common nomenclature implies is that the

people of one’s tribe were People, and all others were something less. Captives

were outside society, but slaves were even further outside the social order. So

as a slave passed from tribe to tribe, my character Buffalo Stone Woman would

have had many instances of rejection and neglect. For most of her adult life,

she would not have been accepted by anyone as a true person, but a creature

somewhere on a level with a dog or other tamed animal.

There were ways to escape the

status of captive, enshrined in solemn ceremony, that could make of a mere

captive a real person by adoption or marriage. Slaves were of a different

nature, “distinguished by the extremity of their alienation from captors’

societies and the exploitation of their labor to enhance the social or material

life of the master,” according to Snyder. Slaves often had a lot of freedom to

come and go in the performance of their duties. And slavery wasn’t a hereditary

condition: children of Indian slaves were not themselves enslaved.

So in Náápiikoan Winter, when Buffalo Stone Woman finds a home at last

among the Piikáni at the base of the Rocky Mountains where although a slave she

has attained the status of a distant wife to the powerful Orator, she wants

never to have to leave this safe haven. She is tolerated, even accepted. She brings

to her new people her skills and her knowledge, which makes them, already

powerful, an even more potent force on the Plains.

|

A photo of a

woman wearing an elk tooth dress, a sign of high regard. Lucy Crooked

Nose - Cheyenne - 1898 - forums.powwows.com

|

No comments:

Post a Comment